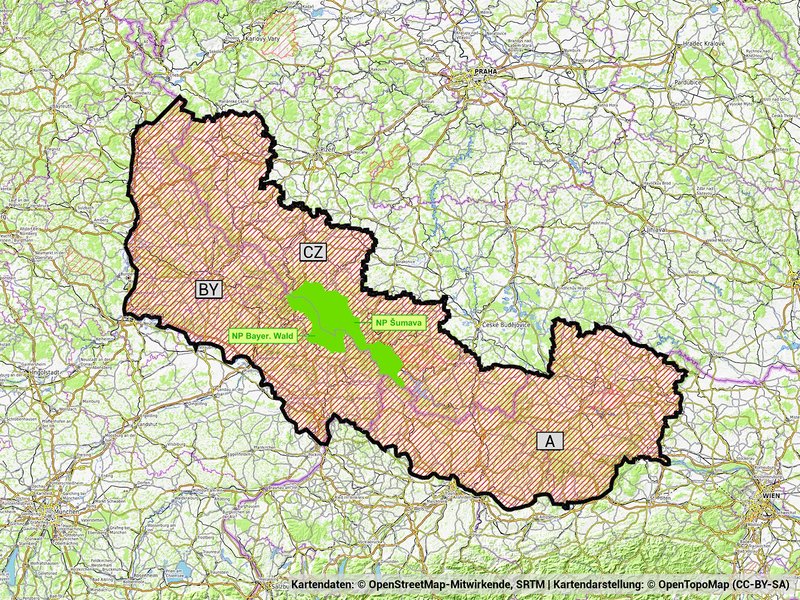

Project area

The project offers the first time the possibility to integrate the knowledge about mushrooms for the cross-border region Bohemian Forest. The region covers the Bavarian Forest in Germany, the Bohemian Forest in Czech Republic down to the Gratzener highland and the Mühl- and Waldviertel in Austria. It includes two national parks and several nature parks and other protected landscapes.

The project area (black border) with the national parks Bavarian Forest and Šumava (green). (Bild: Karasch, Kunze)

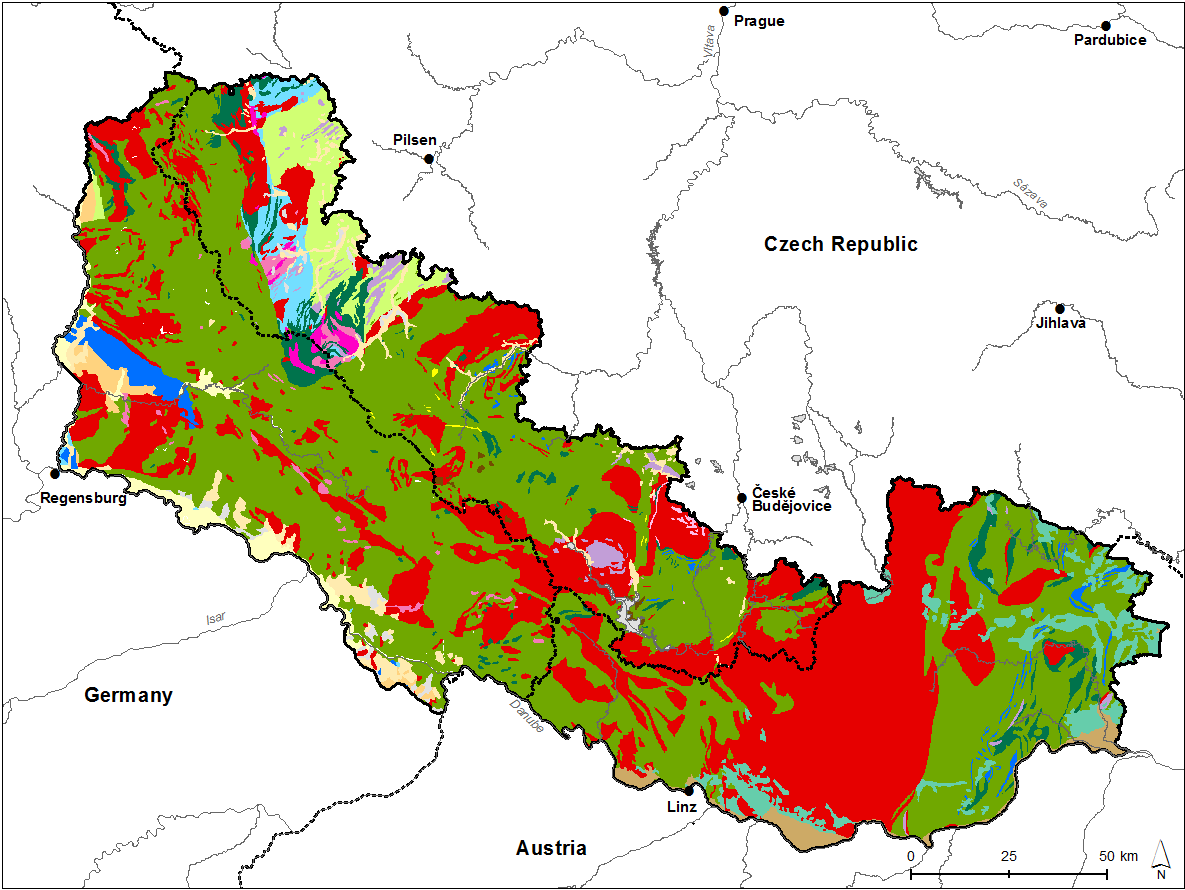

Funga of the Bohemian Forest – geology and ecology

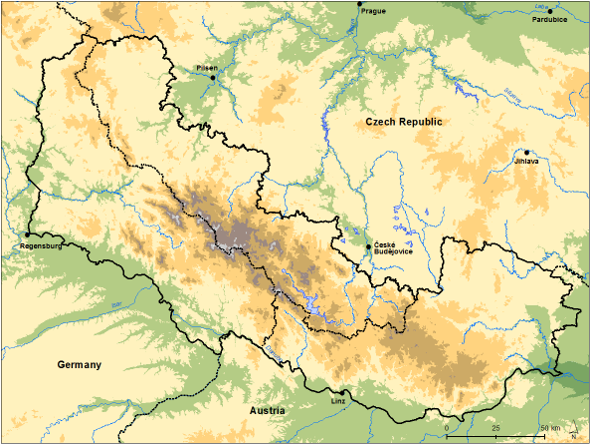

We cordially invite you to explore the „Funga of the Bohemian Forest“ project area. Alas, here we shall go „deeper“ to take a look from below. The geology and ecology are not linked with the political division but consistent over the whole area, and thus, when you are in the Bohemian Forest (no matter if you’re on the Czech, Austrian, or German side), you’re standing in the midst of the Moldanubikum. This is how geologists call a zone of the European bedrock, named after the rivers Vltava (German Moldau) and Danube, flowing within Central Europe in this zone. The bedrock in this zone to a large extent is covered with various sediments, e.g., in the Alpine foreland and in the area of the Swabian and Franconian Alb. However, in the Vosges Mountains, the Black Forest and, of course, the Bohemian Forest the bedrock is uncovered because these mountain ranges were lifted up as tectonic clods and most of the sediments eroded away.

Within the Moldanubikum, the Bohemian Forest is the southwestern margin of a huge complex – the Bohemian Mass – that extends to Prague and Brno on Czech territory. Peter Rothe (Die Geologie Deutschlands [„The geology of Germany“]; primus Verlag) tells us regarding the Bohemian Forest that „[es] dürfte in ganz Deutschland geologisch kaum komplizierter zusammengesetzte Regionen geben“ (throughout Germany, there most likely exist no regions composed in a more complicate way). This complexity is due to the very diverse original material including sandy clays, calcareous rocks, granite, and volcanic rocks – and the vast age. The bedrock was folded mainly during the geological periods of the Devonian and Carboniferous, i.e., 400-300 million years BP; and at least parts of the original material are over 550 million years old, stemming from Proterozoic times. For comparison: folding of the Alps began in the Upper Cretaceous, i.e., ca. 70 million years BP.

Given this enormous age and the long times of erosion, how can some parts of the Bohemian Forest reach higher than others? The main reason is subsequent, differential upheaval. This can clearly be seen when approaching these mountains from southern or southwestern directions. Standing a bit south of the Danube one can discern a series of parallel and rather uniform mountain ranges with the lowest one of ca. 400 m a.s.l. nearby, and the others reaching increasingly high, culminating in the mountain range where the Arber, Rachel, Lusen, and Plöckenstein peak to 1370-1460 m a.s.l. All these mountain ranges are oriented parallel to the northwest-southeastern extension of the Bohemian Forest. Glaciation only was evidenced for the highest peaks, documented by, inter alia, corries and small moraines (e.g. at the Arber). The larger longitudinal valleys follow this orientation of the mountain ranges, and often are utilised by rivers: the upper reaches of the Vltava, Otava, and Große Mühl run from NW to SE, while the Regen runs the opposite direction on half of its course. The Regen valley also is a good example that the valleys pro parte are in fact tectonic faults. Firstly, the Regen valley is following the Pfahl, a fracture formed presumably during the Tertiary and filled with quartz, stretching from Amberg to Linz, and being most apparent in the Regen valley in form of the white „Teufelsmauer“ („devil’s wall“); and secondly, because in a tectonic half trench at the western end of the Regen valley the bedrock lies deeper and, thus, between Schwandorf and Roding there is an area where a cover of sedimentary rocks has survived; these are calcareous rocks and sandstone from the late Jurassic and the Cretaceous.

Besides these regional occurrence of Malm limestone and sandstones (and some other small clods such as the Malm limestones of the Helmberg near Straubing or the Winzer limestone clods near Deggendorf, which were dragged up together with the bedrock during upheaval), rock composition otherwise is characterised by siliceous rocks. Gneiss, mica schist, and granite are the commonest rocks. More locally there are a number of other rocks such as calc-silicates, marble-rich schists, diorites, amphibolites, and gabbros. At the northern edge of the area also greenstones occur. All in all, these rocks are poor or only moderately rich in bases and mostly free of or poor in carbonate. One important exception are the larger valleys reaching into the Bohemian Forest from the southwestern and southern margin, e.g., in the Waldviertel between Mauthausen and Freistadt or north of Straubing in the Kinsach valley: here, the wind sediment loess has been deposited. The pedological situation corresponds to the geological one. Away from the highest mountain ridges, Brown earths and Luvisols are the commonest soil types, while Rankers and raw soils accompany them at shallow sites. At the high ridges mostly mountain Podzols are found, in the valleys Podzols and Gley-like soils, the latter also characterising sites influenced by groundwater. On mountain flanks gaining high precipitation and in corries, ombrotrophic mires have emerged, and minerotrophic mires in the floodplains of rivers and larger creeks. However, mires of both types today are impaired by drainage, agri- and silviculture.

Apart of special sites such as these mire soils or, e.g., dry grasslands on Ranker soil at southern slopes, the potential natural vegetation is characterised by the rather base-poor soils as well as the quite cool climate with high precipitation. The Bohemian Forest would be nearly completely covered by forests. In the lower parts, this would be different types of beech, beech-oak and beech-hornbeam forests that shift to beech-fir forests with raising elevation and, at the highest parts, to spruce and spruce mire forests. This situation has been, of course, strongly altered by man: forests were cleared and arable land, meadows, pastures, and settlements created, spruce was planted even in the lowest regions, fir was driven back, etc. Thus, today there is a very broad range of habitats, reaching from (partly intensively used) agricultural land, over intensively and extensively used woodlands, to the protected forests in both national parks. Regarding mycology, this diversity in site conditions is an important factor just as the richness in indigenous, cultivated, and neophytic plant species is.