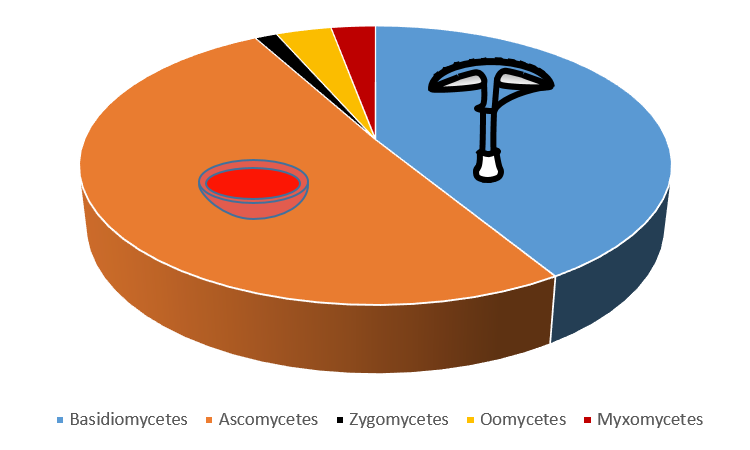

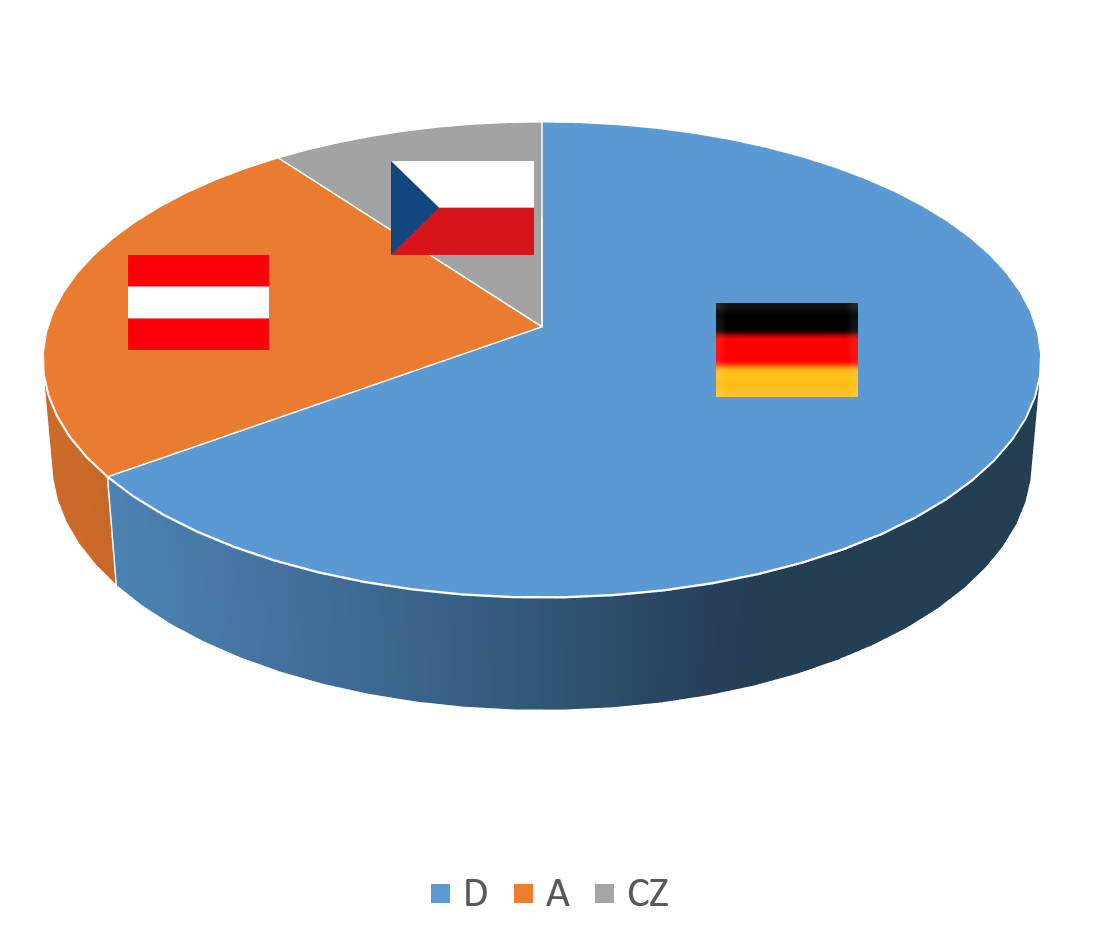

Up to now, around 175 000 fungi were documented, composed by nearly 4 200 fungal species. They were collected by around 110 individuals and institutions. The distribution of the collections into the three involved countries is shown in Fig. 6.

Fungal samples

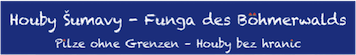

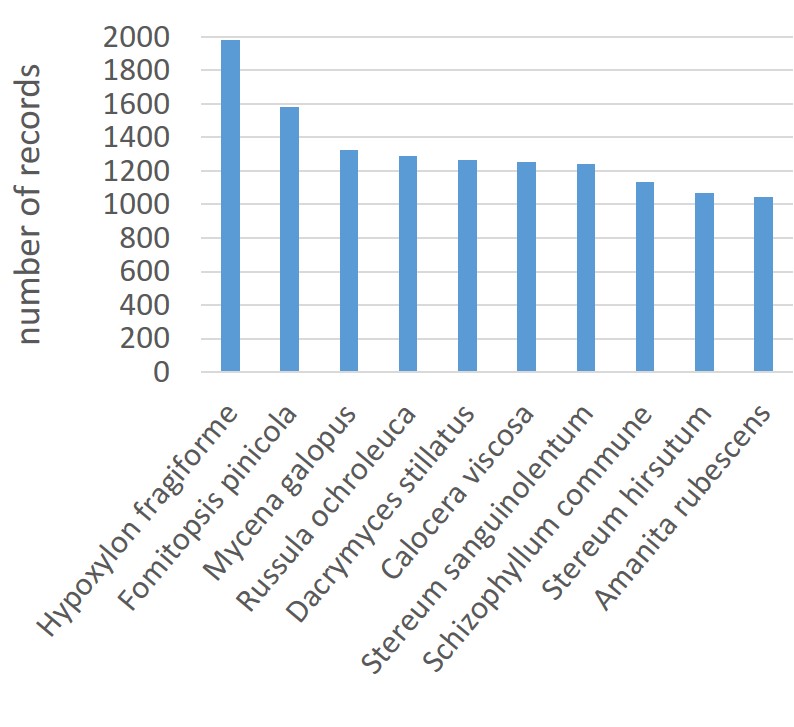

The ten most frequently sampled fungi are shown in Fig. 1. There were more than 1.000 samples of these fungi. 31 % of all species were sampled only once, 39 % were sampled 2-10 times (Fig. 2). A preliminary species list is given here.

|

|

Fungal systematic

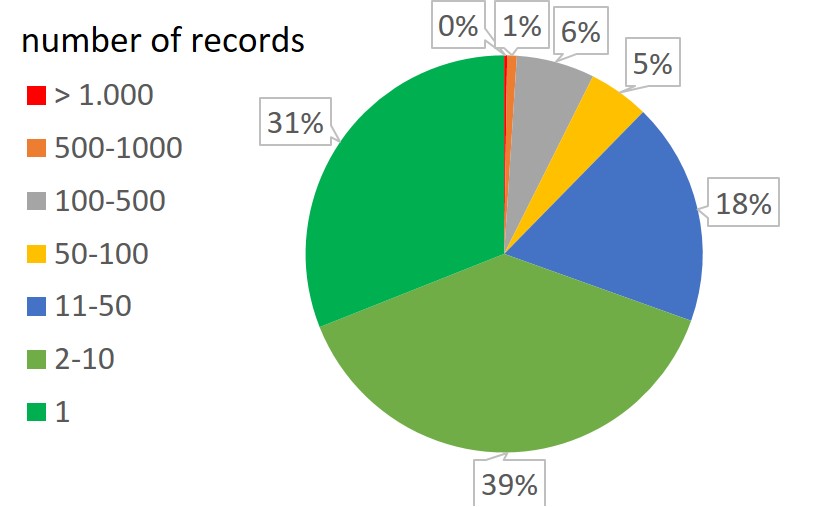

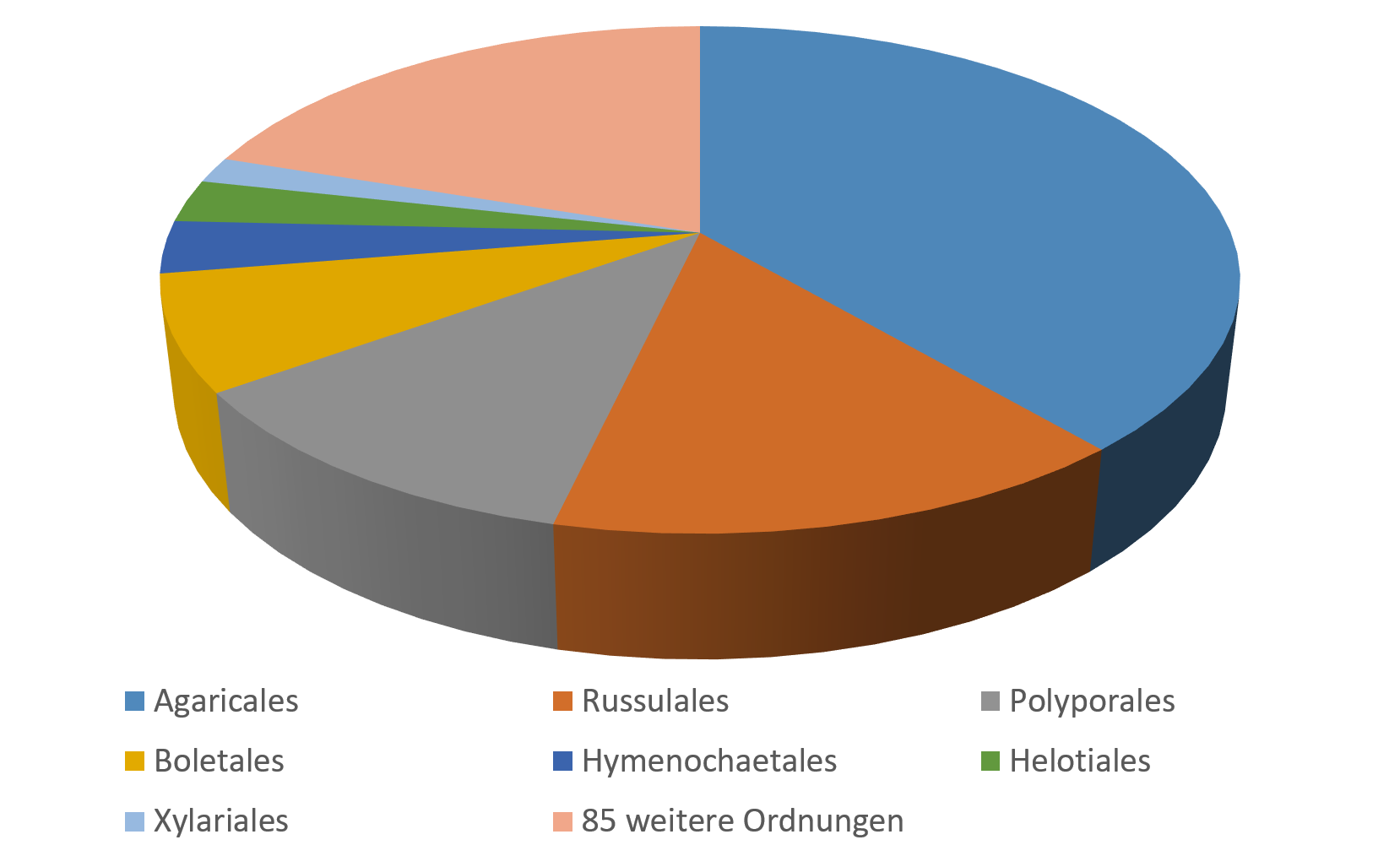

A view on the distribution of records over the bigger systematic groups of fungi (Fig. 3) reflects the collecting preferences of the collectors particularly. It differs from the distribution frequency for records in Germany (Fig. 4). Also, the biggest and most remarkable fruitbodies belong to the three most recorded orders, the Agaricales, Boletales and Russulales. Together they represent more than 60% of all records (Fig. 5).

|

|

|

|

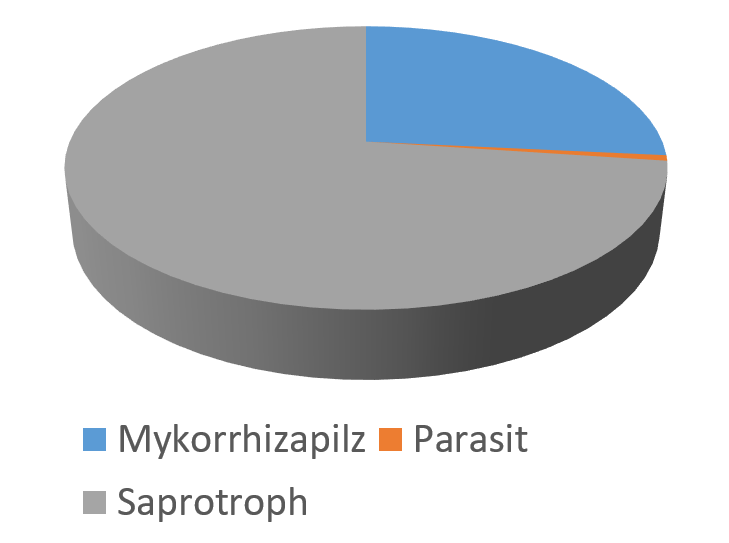

Trophic types in fungi

Fungi differ by their trophic type. In certain cases some species live as symbionts with plants (mycorrhizal fungi) – especially with trees. In other cases species degrade dead plants and other dead organic matter (saprotrophic fungi) and some species feed on other living organisms (parasites). The distribution into these trophic groups is shown in Fig. 7.

|

|

Ecological requirements of fungi

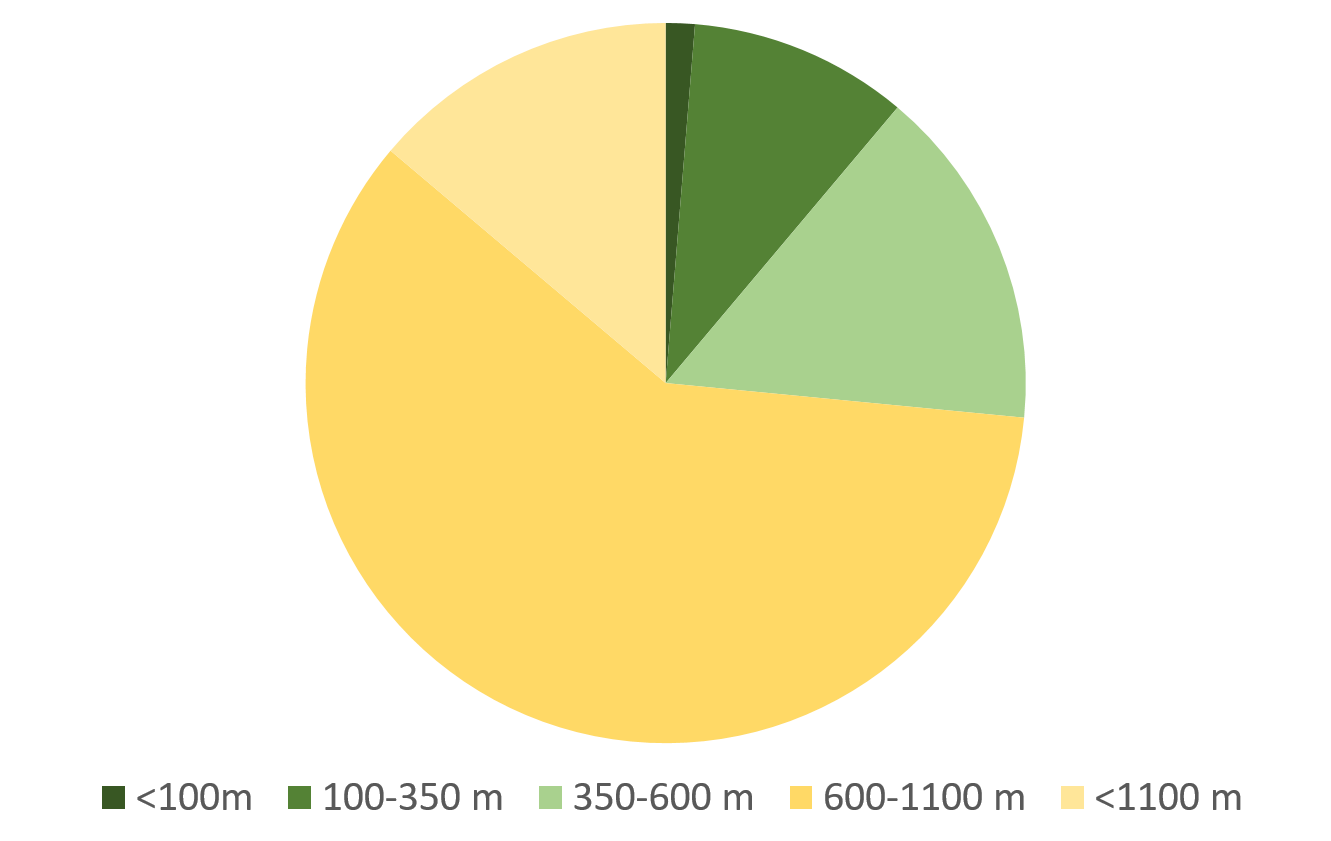

Fungi differ in terms of the demands they place on the environmental conditions in their habitats. A selection is given in Fig. 8-10. According to hight distribution of the massif, most habitats and with thus most of the fungal records, are in the montane locations from 600 metres above sea level.

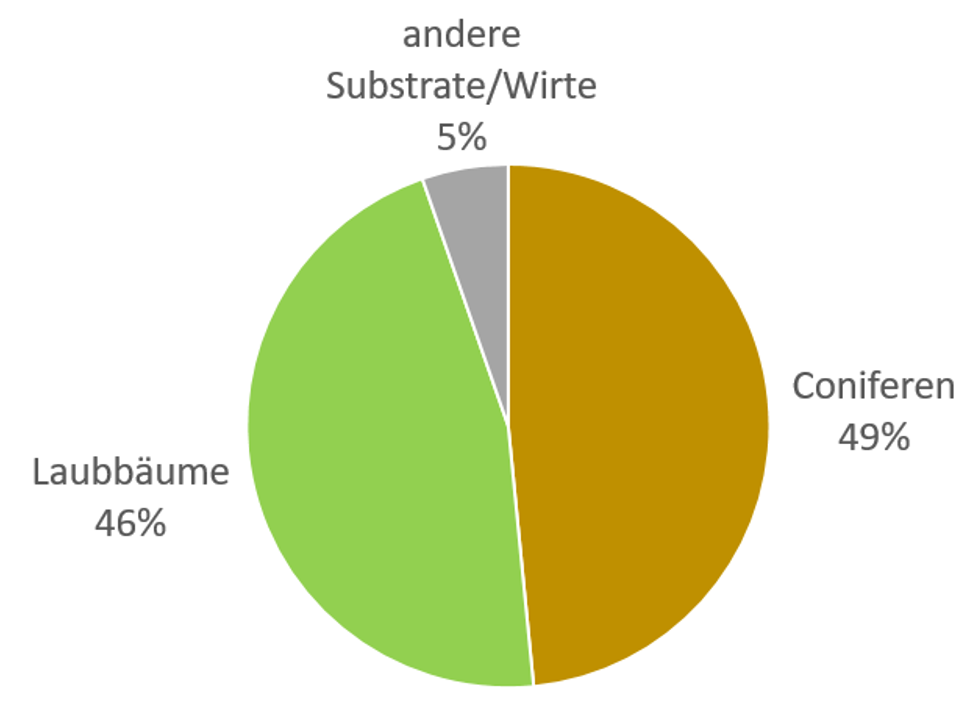

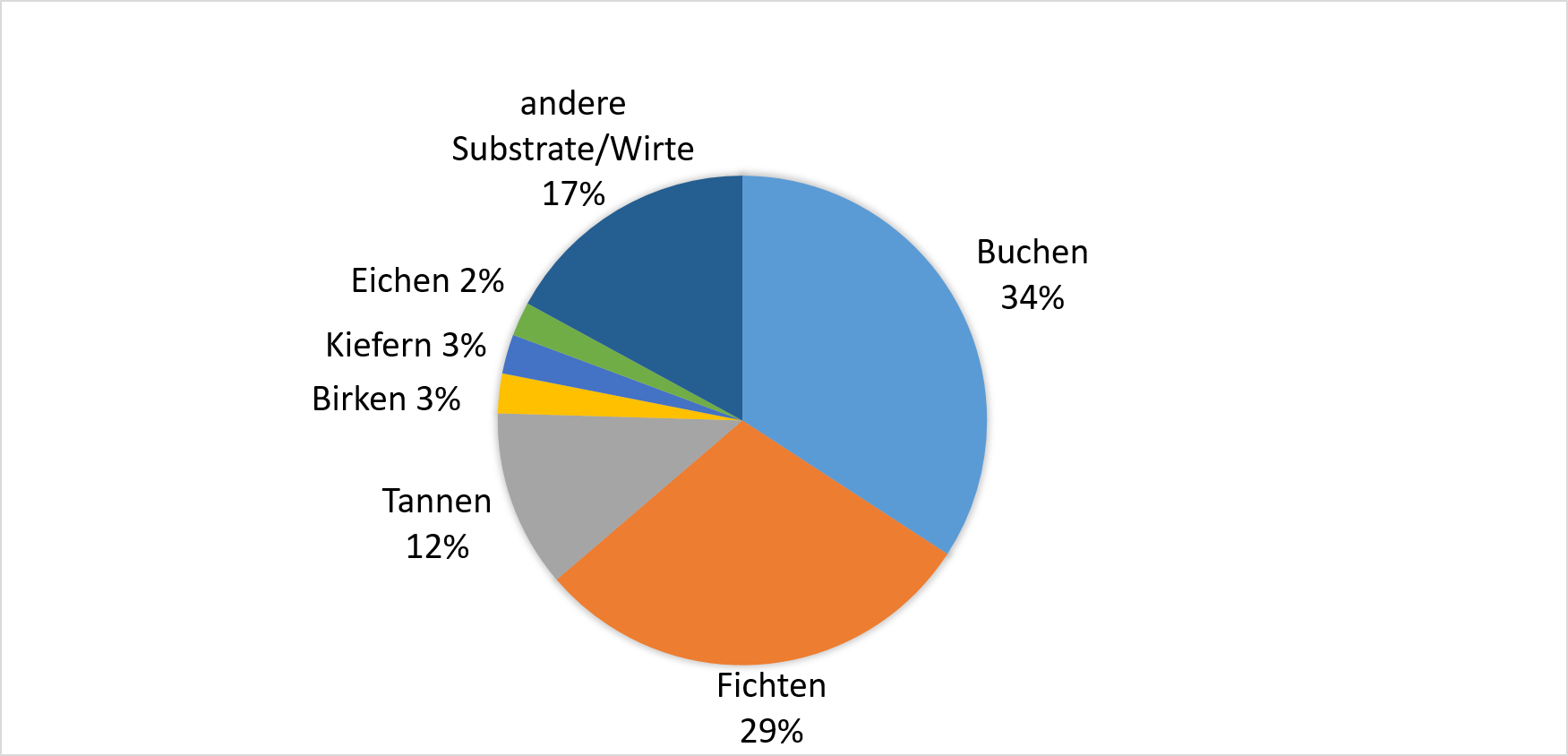

The most remarkable location feature which was given by collectors, additionally to the determination, was the substrate where the fruitbody was found, or the associated tree species of mycorrhizal fungi. With reference to the potential natural vegetation the lower altitudes of the Bohemian forest were dominated by beech or mixed beech stands, because of its geografical position. In higher altitudes conifer stands will dominate. Despite of the forestry history of the region, the actual situation reflects more or less the potential natural vegetation in a broad sense. Regarding the frequency distribution of trees, their associated fungi were found too (Fig. 9). Broad leafed trees were dominated with big distance by beech. Because of foresty, the conifer contingent is bigger than it is naturally expected. Spruce and beech were the most frequent substrates or hosts of the fungi (Fig. 10).

|

|

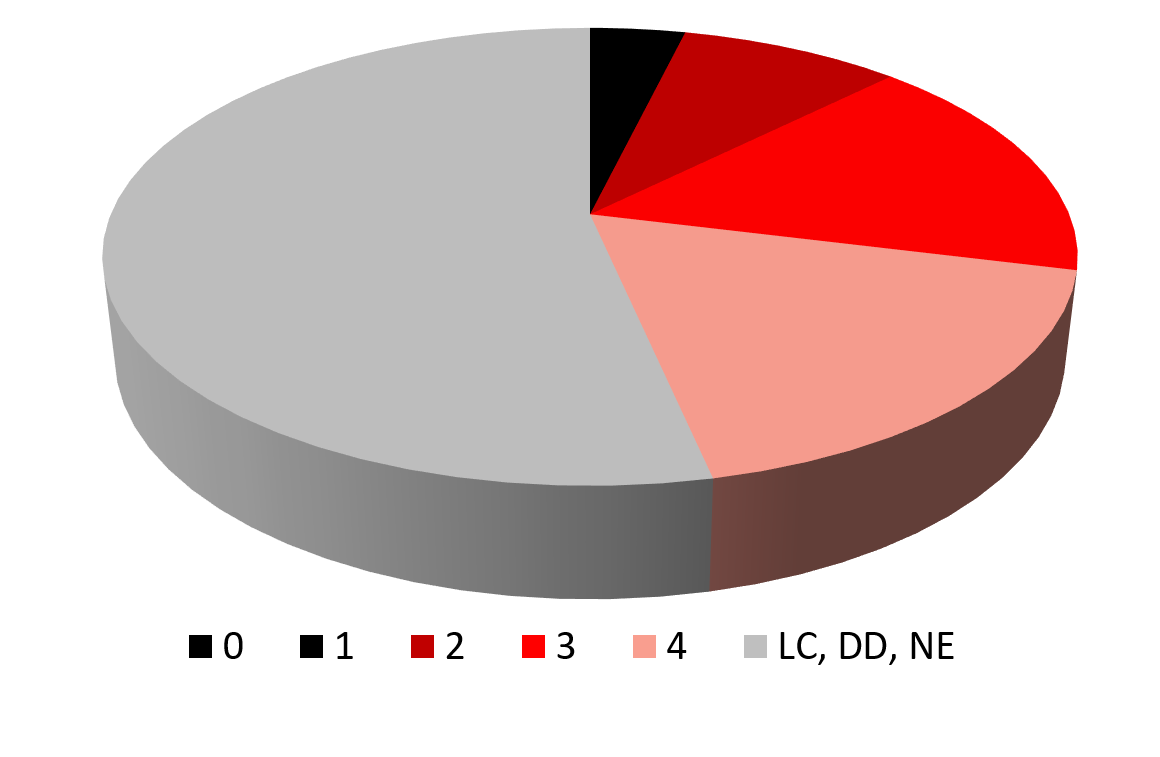

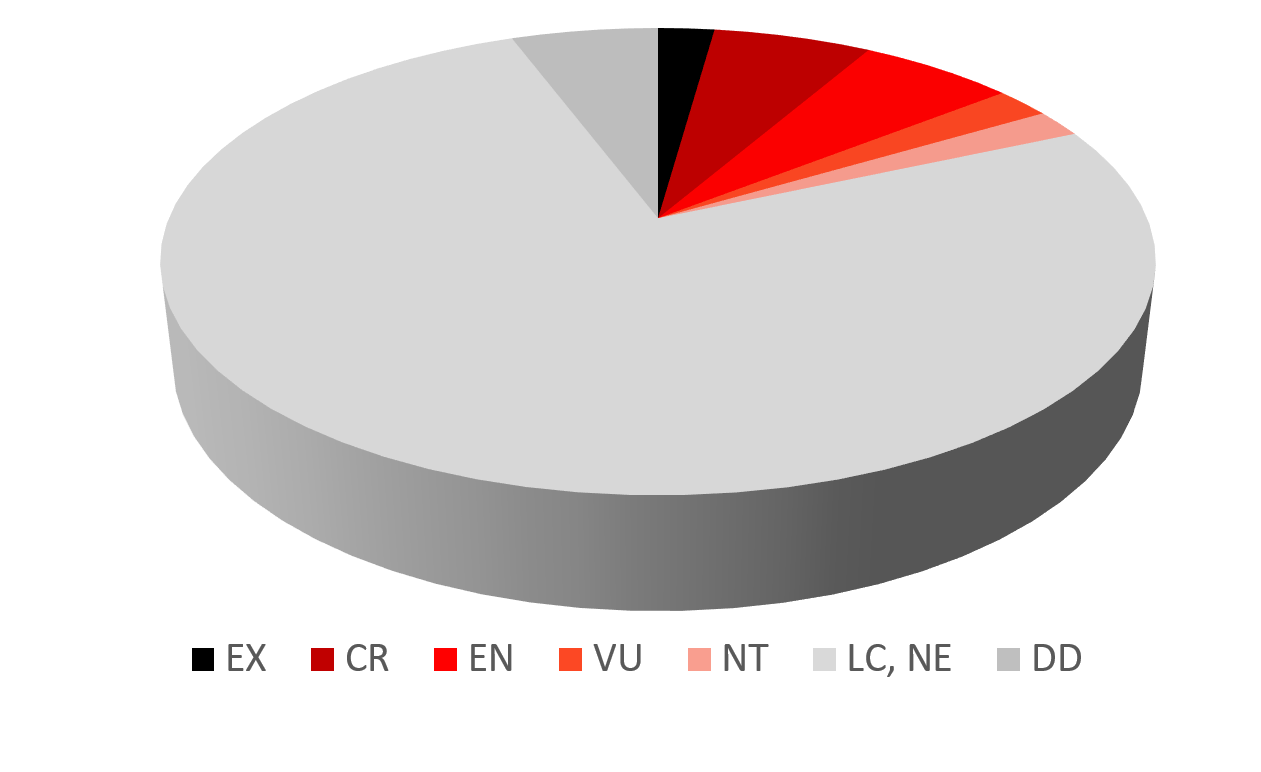

Endangering situation of fungi

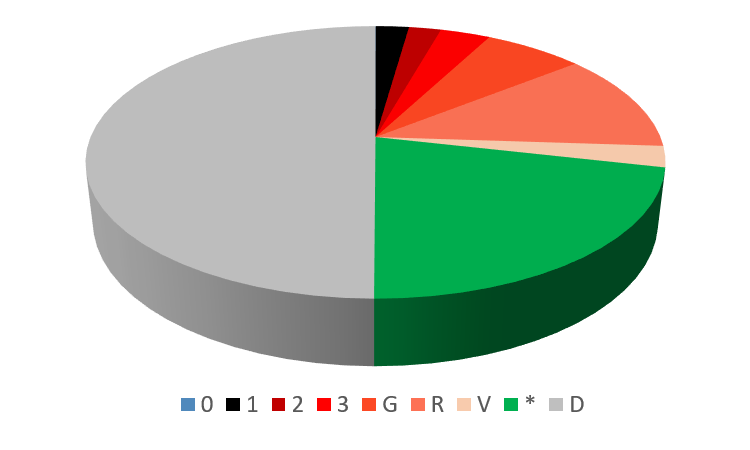

In comparison to other groups of organisms like plants or birds, the endangering situation of fungi is poorly investigated. Thereby, statements about distribution and frequency of many fungi species is not possible or only possible to a limited extent. The evaluation of the endangering situation is presented in the „Red lists“ of endagered fungi in the countries (BfN 2016, Dämon & Krisai-Greilhuber 2018, Holec & Beran 2006). This data has also been transfered to the database and shown together with the species data, which you can select in the menue above. The red list status of the fungi differs between the individual countries (Fig. 11-13).

|

|

|

The red list categories in the three countries (Fig. 11-13) differs, and. unfortunately they are not convertible into one another. While Austria and the Czech Republic oriented their categories on the international IUCN categories, Germany created different ones. Thus a comparison oft he three red lists is limited. Of the more than 2.000 endagered species in Austria, 21% were endangered in Germany and 17 % in the Czech Republic. Germany and the Czech Republic share 29% of the endangered species.

The figures 11-13 show clearly, that the endagering situtation of more than half of the species could not have been evaluated, because its data was deficient due to lack of knowledge and mapping frequence. In the Czech Republic, this percentage is still higher. This is valid for the fungi of the Bohemian forest as well. This clearly shows the necessity of increased mapping. This is right in particular for especially small species which were difficult to find and difficult to determine. This resulted in the low number of records in the group of ascomycetes (Fig. 3). The number of people with well-founded skilled species knowledge and interest in working with difficult systematic groups desperately need to increase. Advanced training courses must be offered more often. Since the number of interested people is not increasing by its own, incentive mechanisms have to be developed.

Special fungi in the Bohemian forest

Within the project area several stands with native character or old growth forests are preserved. They are located in the core areas of both national parks or in nature reserves. Additionally, there are natural forest reserves in Germany, which were attended by the LWF for research. In the old growth forests fungal species grow, which were very rare or extinct in other more intensiv managed forests. These are called relict species or near-natural indicators. The project published a booklet, where a part of these species were presented (Šumava Nationalpark 2019).

References:

Bundesamt für Naturschutz (2016): Rote Liste gefährdeter Tiere, Pflanzen und Pilze Deutschlands - Pilze (Teil 1) - Großpilze, Bd.8.Naturschutz und Biologische Vielfalt 70 (8). 440 S.

Dämon W, Krisai-Greilhuber I (2018): Die Pilze Österreichs. Verzeichnis und Rote Liste 2016. Teil Makromyceten,Österr. Mykolog. Ges., Wien. 609 S.

Holec J, Beran M (eds.) (2006): Červený seznam hub (makromycetů) České republiky [Red List of fungi (macromycetes) of the Czech Republic]. Příroda, Praha 24: 1-282

Karasch P, Striegel M, Pouska V, Bässler C und Krisai-Greilhuber I (2019): Pilze im Böhmerwald - Besonderheiten, Klassiker und Naturnähezeiger. Verwaltung des Nationalparks Šumava. 40 S.